The fight for equal marriage at the courts and polls in the Virgin Islands

Plus, a crash course in 25 UK jurisdictions and 1000 years of British history

A case seeking to legalize same-sex marriage in the British Virgin Islands finally began hearings yesterday, after nearly a year of delays caused by some procedural shenanigans on the part of the religious group seeking to maintain the existing ban on same-sex marriage. The hearing is expected to take four days, with judgment to follow some time later (probably several months).

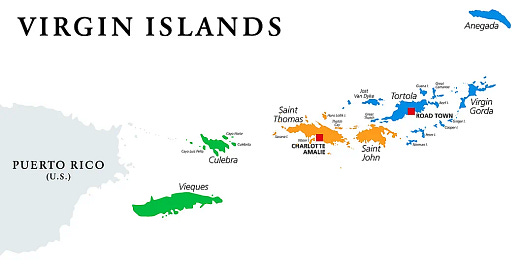

First, some quick geography:

The Virgin Islands are an archipelago east of Puerto Rico, that were colonized by the British, Danish and Spanish (with shorter periods of rule by the Dutch, French, and Scottish). The British Virgin Islands are the territory we’ve been talking about (although they rather confusingly dropped the word “British” from the official name). The Danish sold their Virgin Islands to the USA in 1917, and they became the Virgin Islands of the USA (and got same-sex marriage in 2015). The Spanish Virgin Islands are a part of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, which is also a US territory that got same-sex marriage in 2015.

“But wait,” you ask. “Doesn’t England already have same-sex marriage? Shouldn’t it be legal in all British territories?”

Well, here’s where it gets complicated. Buckle up for a crash course on a thousand years of British political history and what may be the silliest constitutional design of any modern democracy. I promise this is all going to be relevant.

“England” is actually one of the four countries that make up the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland – UK for short. The English have spent nearly a thousand years conquering territories near and far, eventually amassing the largest empire known to human history.

Nearby, England absorbed Wales and conquered Ireland, and then was united with Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707, then the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in 1801. Most of Ireland became independent, but Northern Ireland stuck with the UK. Northern Ireland, Wales, and Scotland each have varying levels of devolved responsibilities from the central government (England does not have its own Parliament, however). The UK Parliament at Westminster and the government also retains the power to overrule the devolved governments in certain circumstances, as the UK government recently did to block a legal gender recognition law in Scotland.

The British crown also ended up with three nearby islands as self-governing dependencies: Isle of Man, Jersey, and Guernsey. The latter Island has two self-governing dependencies of its own: Alderney and Sark. None of these is part of the UK, but the UK often represents them in foreign affairs. Again, I promise this is all going to be relevant.

And now the territories. While the UK divested itself of most of its colonial empire, it maintains 14 territories around the world, either because the local population has chosen to maintain their ties to the UK, or because the territory is uninhabited (to perhaps over-simplify).

Most of the territories are basically self-governing, albeit the UK government maintains some reserved rights to act for the local governments (and before you ask, no, the territories do not get representation in the UK Parliament). This part’s important.

Ok, so same-sex marriage? Well, the entire UK has it now. Parliament passed it into law for England and Wales in 2014, and the Scottish Parliament followed soon after. Parliament later acted to legalize it in Northern Ireland in 2020 during a period when that province’s elected government wasn’t functioning (long story). The crown dependencies each legalized it between 2016-2020.

Of the 14 territories, 8 currently allow same-sex marriage. The UK government extended same-sex marriage to the 4 uninhabited territories it governs directly: British Indian Ocean Territory, British Antarctic Territory, Akrotiri and Dehkelia military bases on Cyprus, and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands. Territorial governments passed their own same-sex marriage laws in Pitcairn Islands, Falkland Islands, Gibraltar, and in the separate local governments of St. Helena, Ascension Island, and Tristan da Cunha (which is considered one territory).

The other six territories, all in the Caribbean and Atlantic, do not allow same-sex marriage. But one did for a while.

Bermuda, in the mid-Atlantic, allowed same-sex marriage after the territory’s courts repeatedly ordered it to do so in 2017 and 2018. But that came to an end in 2022, when the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council – a sort of Supreme Court for the territories and certain other former territories located in London – overruled the local courts and said there was no right to same-sex marriage under Bermudian law. For good measure, the Privy Council also ruled that there was no right to same-sex marriage in the Cayman Islands either. (I’ll likely do an explainer of the JCPC at some point, too.)

Both territories now allow a form of registered civil partnership for same-sex couples, but not without controversy. In the Caymans, the local legislature actually voted down a proposed domestic partnership bill, only for the UK-appointed Governor to impose a civil partnership law by fiat. This reserved power is meant only to be used for issues of vital importance like maintaining rule of law and international obligations. Here, the Governor argued that the territory was required to pass a civil partnership law after local courts found that registering same-sex families was an obligation under the European Convention on Human Rights.

Ok, let’s back up one more time. The ECHR is an international human rights agreement that has been joined by every country in Europe except Russia, Belarus, and the Vatican.1 To be absolutely clear, it has nothing to do with the European Union, which is why it still matters to the UK despite Brexit. And although it says “European” right there in the name, it applies equally to territories outside of Europe governed by member states. And, over the last decade, the European Court of Human Rights has progressively found that states are obligated to give legal recognition to same-sex couples – albeit that it has not yet found a right to same-sex marriage under the treaty. This may be the subject of a whole separate column.

Ok, so now you’re thinking, if the ECtHR has established that the civil partnerships are required at a minimum under the convention, and the Privy Council has ruled against marriage in the territories, isn’t this an open-and-shut case for the remaining four territories — i.e. no to marriage but yes to civil unions?

Fortunately, no, it isn’t.

While the UK government could (and probably should) use its reserve powers to impose a civil partnership law on the other four territories – the Virgin Islands, Turks and Caicos Islands, Montserrat and Anguilla – it hasn’t yet. In fact, this wouldn’t even be the first time the UK government has intervened to protect LGBT rights in its territories. Back in 2000, the UK (under the Blair Labour government) intervened to strike down sodomy laws in the territories in order to meet its commitments under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Today’s UK Tories are probably trying not to rock the boat until they’re forced to by court order, as they were in Caymans. That’s leaving local LGBT couples out of luck.

Meanwhile, it’s not actually a settled matter that the Privy Council will not find a right to same-sex marriage in these territories. That’s because the Privy Council isn’t like the US Supreme Court, mediating disputes in states that share a common constitution. Each territory has its own constitution with slightly different wording, and that’s what the Privy Council has to refer to for each decision. The UK Virgin Islands Constitution actually describes a right to marry that is much more expansive than either Bermuda or Caymans’ constitutions, and it also includes an explicit right to freedom from discrimination based on sexual orientation, unlike those territories. The Privy Council may not be as willing to block same-sex marriage here, if a case is brought to them (as seems likely, eventually).

In addition, the cases from Bermuda and Cayman aren’t even finished yet. After losing at the Privy Council, the Bermuda plaintiffs took their case to the ECtHR. The European Court has just taken up the case and asked the UK to explain itself. Could this be the case that finally gets the ECtHR to find a right to same-sex marriage? I may have to come back to this question.

On top of all of this, the UK Virgin Islands government is now planning to hold a referendum on same-sex marriage and domestic partnerships that it hopes will pre-empt or put pressure on any court decision. We still don’t have any details on this, like when it will be held or what the question(s) will be.

And if you’re wondering why there haven’t been more test cases from the other territories, just bear in mind that these are very small territories. There’s only 5,000 people on Montserrat and 38,000 in Turks and Caicos. It can be quite expensive to pursue a case (especially to the Privy Council) and incomes are much lower than they are in the rest of the UK. And many LGBT people in these territories simply leave before it can become an issue.

Let’s circle back to all those mini-jurisdictions in and associated with the UK – that was 25 in all if you were keeping count. Even though same-sex marriage is settled law in the vast majority of them, there are huge differences related to LGBT rights in each jurisdiction. This extends to issues like non-discrimination law, legal gender recognition, adoption and family planning, conversion therapy (which is not currently banned anywhere in the UK, but will eventually have to be done jurisdiction-by-jurisdiction).

As always, I’ll keep you posted as more develops.

—

Thanks for reading. Let me know if there are any other topics related to LGBT rights and same-sex marriage that you’d like to see a deep dive on!

Kosovo is de facto under the jurisdiction of the ECtHR, and is in the process of joining the Council of Europe. Kazakhstan is also not part of the ECHR, but it’s only slightly in Europe.